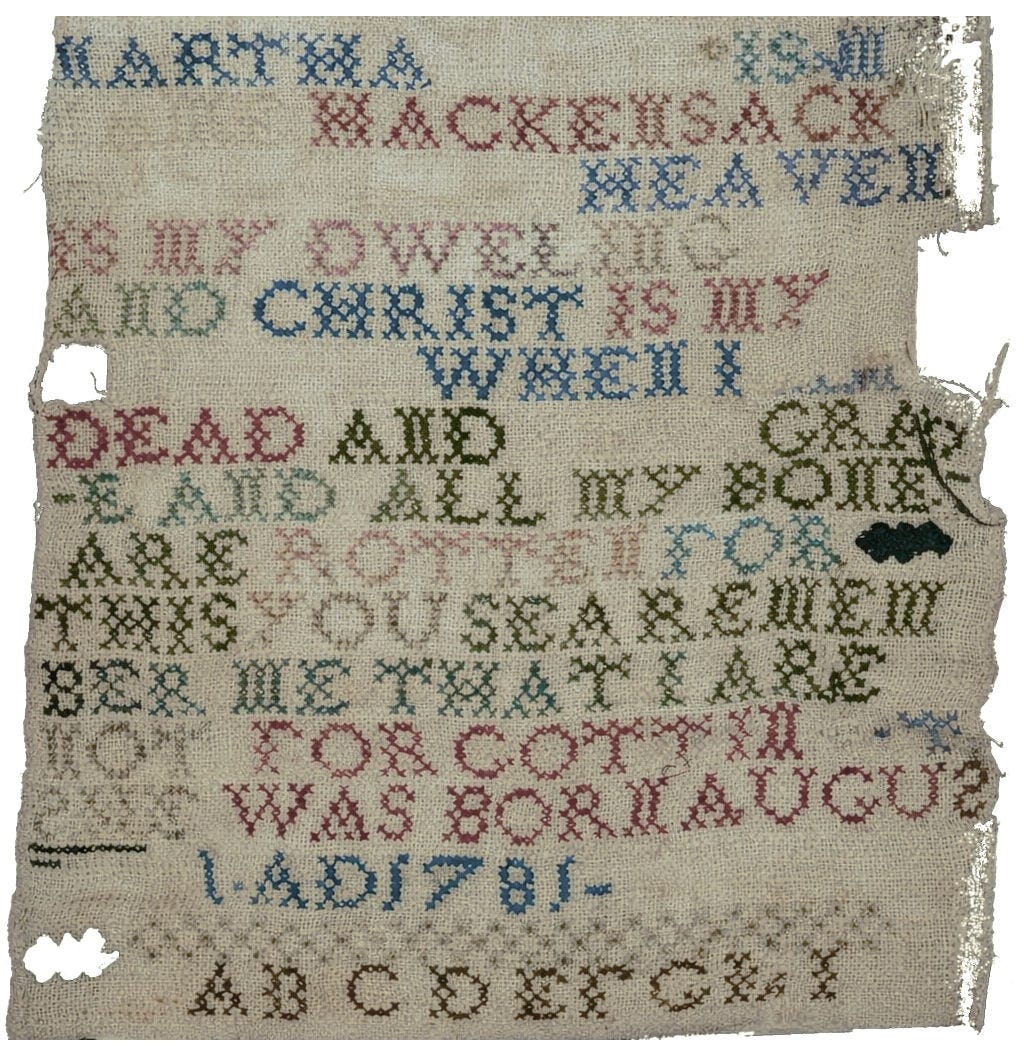

12. Martha Earl Sampler

“Remember me.”

Even when a sampler is stitched with a name and a date, we still so often have no idea who the girl was who made it. A common note in online museum collections about the maker of a given sampler is “Nothing is known about the life of...” All we know is that, centuries ago, a girl sat down—willingly or unwillingly—and made this thing requiring focus and precision, and it might have been the only time in her life when she named herself in her own hand.

Across socioeconomic lines, from charity schoolgirls demonstrating their employable skills to daughters of wealthy families signaling their refinement, most girls made samplers in the early centuries of the country. Many of them survive because they were valued items, sometimes framed and hung in the house.

In the 1970s, the National Archives photographed millions of historical documents from families who had applied for pensions based on service during the Revolutionary War. In a few cases, researchers were surprised to discover samplers tucked between the handwritten depositions and affidavits. Because documentation could be difficult to come by, families would occasionally produce unofficial records, including samplers, as proof of identity, which the government accepted.

This sampler by Martha Earl was such a document. It is a beginner’s piece of work, likely made when she was about six years old, around 1787. Many samplers include verses concerning death, and Martha’s poignant text demonstrates an awareness, even at her young age, that life is fleeting:

Martha Earl is my/ name

Hackensack is/ my station

Heaven/ is my dwelling [place]/

And Christ is my [sal/v]ation

When I [am]/ dead and in my grav/

- e and all my bones/ are rotten

For/ this you sea remem/ber me

That I are/ not forgottin/

She was born August/ 1 AD 1781

ABCDEFGHI

Links:

Jennifer Davis Heaps, “‘Remember Me’: Six Samplers in the National Archives,” National Archives Prologue magazine, Fall 2002

Michelle Galler, “Samplers: The Artwork of Children,” The Georgetowner, July 11, 2018.

This post is part of The American 250, a series featuring 250 words on 250 objects made by Americans, located in America, in honor of the country’s 250th anniversary. Through December 31, 2026.

Too many emails? Instructions for receiving a weekly summary can be found here.

I’m looking for ideas for this series — have something you’d like me to consider for inclusion? Please feel free to leave a comment!

"Man's work is sun to sun, but women's work is never done."

A young girl starts on her journey to womanhood with cross-stitched samplers, progressing and acquiring skills in crocheting, knitting, embroidery, spinning, weaving, sewing, tatting, quilting, and other crafts based on textiles. There are many American-made examples in the Bayou Bend collection of MFAH, collected by Ima Hogg.

One of the most poignant, unusual and Houston-significant of these is a large oval cloth, hand-painted and embroidered with the inscription, "Phillis Wheatley Negro Servant to John Wheatley of Boston MDCCLXXIII." It is a tribute to the first African-American female published poet. The original image was an engraving circa 1773 attributed to Scipio Moorhead, an enslaved African-American man.

Phillis Wheatley High School, the first high school for blacks in Houston, was named for her.

Here is a link to the MFAH object:

https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/76996

and a link to the original print in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art with a detailed description:

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/396463

oh god so good Rainey, thanks for sharing. I often get so many emails that I miss your posts...but whenever I am able to click on one to see what you are writing about, I am always so glad I did.

Yesterday I got a note from a friend about a new film- 'The Sound of Falling' This comes to mind after reading your words. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/14/movies/sound-of-falling-mascha-schilinski.html?unlocked_article_code=1.ElA.GHd4.EiQyJgUm539a&smid=url-share